Great news for Mono Lake’s tributary streams!

On October 1, the California State Water Resources Control Board issued Order 2021-86 amending the Mono Basin water rights of the City of Los Angeles to incorporate extensive new requirements that maximize the restoration of the 20 miles of streams, forests, and fisheries that lie downstream of the Los Angeles Aqueduct diversion dams.

The Board’s landmark action is built on a voluntary settlement agreement, which you can read more about below, between the Mono Lake Committee, DWP, California Department of Fish & Wildlife, and California Trout. The agreement set forth mutually agreeable ways to advance stream restoration and was submitted to the State Water Board in 2013.

When the Los Angeles Aqueduct was built in the 1930s, it had one purpose: take all the water from four of Mono Lake’s tributaries and deliver it to the city of LA.

The 2013 Mono Basin Stream Restoration Agreement changes that singular purpose into two: to deliver water to the people of LA and to protect and restore Mono Lake and the Mono Basin streams providing that water.

The innovative Stream Restoration Agreement promises a healthy future for 19 miles of Rush, Lee Vining, Parker and Walker creeks and certainty about the restoration of their fisheries, streamside forests, birds, and wildlife.

Road to the Stream Restoration Agreement

The groundwork for the Agreement was laid with the two restoration orders that the State Water Board issued in 1998, requiring DWP to implement a restoration plan for the Mono Basin’s streams and waterfowl habitat.

The orders also launched a decade-long study of the conditions of Mono’s tributaries, conducted by independent Stream Scientists appointed by the State Water Board. After the study concluded in 2010, the Stream Scientists recommended changes to the way DWP operated to ensure that the streams would truly be restored, with guidelines for monitoring that progress.

DWP objected to those recommendations, and so the State Water Board directed DWP, the Mono Lake Committee, California Trout, and the California Department of Fish & Wildlife to work together to resolve their disputes. The process took three years and resulted in the 2013 Stream Restoration Agreement.

Highlights of the Stream Restoration Agreement

Stream Ecosystem Flows

At the heart of the Agreement are specific day-by-day, stream-by-stream flow recommendations for Mono Lake’s tributaries. These flows are called Stream Ecosystem Flows (SEFs). SEFs mimic natural runoff patterns and activate the natural processes that will restore the streams; implementing them is the single most important action necessary for stream restoration.

The flow requirements set in the 1990s were made up of just six different components during the year. SEFs contain up to 14 components, each customized to the creek for which they were designed.

To determine SEFs, the Stream Scientists identified the natural stream processes that, once put into motion, will restore healthy stream habitat and conditions for trout. Examples of those natural processes include flooding, floodplain seeding, channel shaping, pool scouring, gravel movement, groundwater recharge, and temperature maintenance. The scientists then determined the volume and timing of water needed in the streams to activate the processes.

For example, a thriving cottonwood-willow forest depends on springtime floods that spill over stream banks; these floods deposit sediment and allow seeds to germinate across the floodplain. Trout favor deep pools, and to scour those out, the rate of water flow needs to be high enough to have the energy necessary to move cobbles and even boulders. In the winter, low base flows benefit fish, reducing the stress on them during the coldest months of the year.

The Agreement has page after page of tables full of streamflow specifications—creek by creek, numbers for spring snowmelt floods, for winter base flows, for spring seeding, for every type of wet and dry year the Mono Basin experiences.

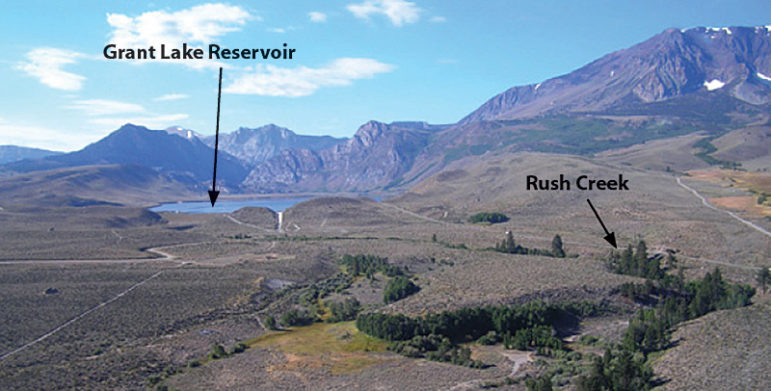

Lee Vining Creek, Parker Creek, and Walker Creek will benefit from SEFs right away. On Rush Creek, however, DWP must alter a major structural impediment before SEFs can be implemented: Grant Lake Reservoir Dam.

Grant Lake Outlet

SEFs cannot currently be delivered to Rush Creek below Grant Lake Reservoir because of the limitations of the aqueduct’s World War II-era infrastructure, specifically the lack of an adequate outlet facility.

A key element of the Agreement is DWP’s commitment to invest an estimated $15 million to modernize infrastructure at the Grant Dam by building a new Grant Outlet structure. This will give DWP the capacity to deliver the required SEFs to Rush Creek.

The new outlet will physically and symbolically show that the Los Angeles Aqueduct can achieve two goals: to deliver water to the people of LA and to protect and restore Mono Lake and the Mono Basin streams providing that water.

Streamlined monitoring, collaborative operations

The Agreement requires ongoing fishery, stream, and waterfowl monitoring to make sure restoration is proceeding correctly. It also specifies that Mono Lake monitoring must continue, conducted by expert scientists who ran the program for decades until DWP replaced them with in-house staff.

When stream monitoring indicates that the restoration process should be adjusted to optimize the creeks’ recovery, the Agreement authorizes a strategy called adaptive management. Adaptive management provides the flexibility to adjust SEF timing, duration, and magnitude to maximize the ecological benefit. The Agreement contains limitations to ensure that any adjustments do not violate established minimum flows or reduce water exports to Los Angeles.

To manage the required monitoring, the Agreement creates a new oversight team made up of DWP, the Mono Lake Committee, the California Department of Fish & Wildlife, and California Trout. DWP must provide funding for a comprehensive list of monitoring tasks and the management team will make sure those tasks happen.

The Agreement also directs a collaborative approach for multi-year and annual Mono Basin aqueduct operations planning, which ensures that expertise from all parties will be taken into account. Operating the aqueduct to achieve both stream restoration and water export goals will take careful planning and coordination and the Mono Lake Committee will play an active role.

Persistence for the streams

After the Agreement was signed by all parties and approved by the DWP Board of Commissioners in 2013, the Mono Lake Committee organized a celebration to mark the occasion, attended by DWP officials, all Agreement parties, and many dedicated Mono Lake Committee members.

It seemed like everyone was ready to move forward with implementing the Agreement, but DWP has held up the process in several significant ways.

DWP delays State Water Board on new water rights license

The Agreement depended on a new water rights license for DWP, issued by the State Water Board. The license must include both the new provisions of the Agreement as well as all existing requirements that are scattered throughout State Water Board documents, decisions, and orders. During the meticulous process of bringing all license requirements together, the Mono Lake Committee made sure that no requirements were lost.

After several years of DWP dragging its feet and the Mono Lake Committee and State Water Board prodding, DWP refused to produce the one remaining environmental document needed for the Grant Outlet.

Grant Outlet planning grinds to a halt

Under the terms of the Agreement, DWP took the lead in designing the Grant Outlet facility and planned to construct a notch in the existing overflow spillway to create the ability to release regulated flows from the reservoir into Rush Creek.

In 2015 DWP shared engineering details, which showed a conceptual plan for installing a pair of 12-foot-tall variable-position gates called Langemann gates into the notched spillway to allow the controlled release of water. Core samples had been drilled, geotechnical data analyzed, and engineering drawings were at that time about 30% complete.

However, more work on the Grant Outlet wasn’t required until DWP’s new water rights licenses were issued by the State Water Board. With the license process delayed, progress on the Grant Outlet also ground to a halt.

2020 hearing

The Agreement deferred the scheduled State Water Board hearing on DWP’s water licenses from 2014 to 2020, to allow the Grant Outlet to be constructed and SEFs to be implemented without getting caught up in new legal proceedings. But, for the reasons above, the Grant Outlet has not been constructed and SEFs have not been implemented.

In addition to delaying the license process overall, DWP also began to insist that the Agreement promised no changes to its water exports from the Mono Basin, regardless of a hearing on the matter. Since no such thing was written into the Agreement, DWP is essentially attempting to rewrite a signed document to suit itself.

Mono Lake Committee stands firm

Based on our long history with DWP, the Mono Lake Committee was not surprised by DWP’s tactics to delay the implementation of the Stream Restoration Agreement. We deployed technical experts to keep the process moving, stayed in close contact with the State Water Board, and continued to remind DWP of its commitments.

In 2019 we got the Agreement SEFs implemented on Lee Vining, Parker, and Walker creeks and made sure that the Mono Lake monitoring program was returned to scientists with limnological expertise instead of DWP’s in-house staff.

The State Water Board has grew increasingly impatient with DWP’s foot-dragging and in 2020 itself replaced DWP as the lead agency working on the long-delayed environmental report.

As always, especially in the face of DWP’s years-long delays, the Mono Lake Committee is committed to the best possible future for Mono Lake and its streams, and we will make sure that the streams receive the restoration they still need.

More detail about the Stream Restoration Agreement

RELATED RESOURCES: Diving into the Stream Restoration Agreement | Celebrating the Stream Restoration Agreement | Read the Agreement document in full | 2010 Synthesis of Instream Flow Recommendations Report

Related Posts

Top photo by David Gubernick.