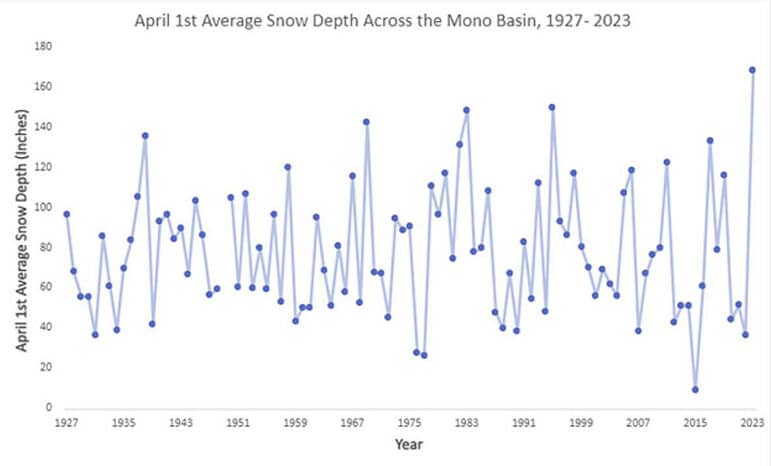

Over the past few weeks, I have been working with the Mono Lake Committee’s Information & Restoration Specialist, Greg Reis, on organizing and updating our snow data records. In the aftermath of a winter that nearly buried Lee Vining, it has been fun looking at historic trends and what we used to think of as record breaking.

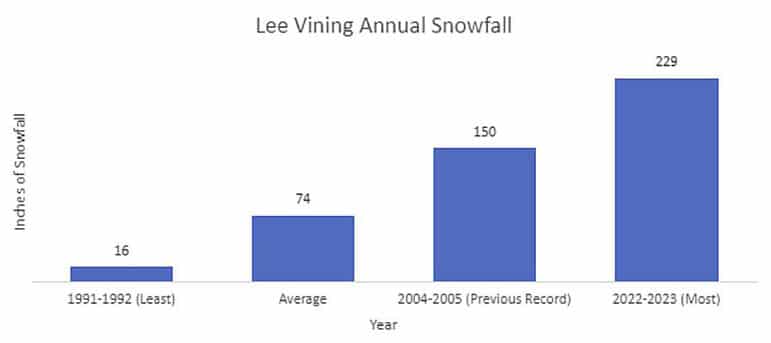

The average annual snowfall in Lee Vining from 1990 to 2023 is 74 inches. During this past winter we received a whopping 229 inches, soaring above what is considered to be normal. The Sierra Nevada has relatively mild temperatures and large quantities of snowfall during the winter months. While the large quantities of snowfall typically provide a picturesque playground for skiers, snowshoers, and snowboarders alike, last winter was more than anyone bargained for.

So, if snow is extremely common here in the Eastern Sierra, what caused the biggest snowpack on record last winter? The primary culprit is a rapid succession of atmospheric rivers. Now you may have heard this term thrown around, but to define it loosely, you can think of them like rivers in the sky that transport water vapor out of the tropics into other regions. Atmospheric rivers are entirely normal in weather patterns and are responsible for much of the precipitation the western United States receives. During this past year, we received a parade of atmospheric rivers that brought massive amounts of water vapor to our region, one after the other. From November 31, 2022, to March 31, 2023, 31 atmospheric rivers hit California. Back-to-back atmospheric rivers are not entirely unheard of, but on this scale, they are certainly rarer and bring significant impacts.

As human activities are increasingly heating the atmosphere, the warmer air can hold more moisture. Storms all over the world, including the ones that tear across the Pacific Ocean toward the Sierra, will be more precipitation-heavy and intense. California has swung between wet and dry periods for a long time, and we are already seeing this variability become more amplified by climate change.

While most people did not experience feelings of joy having 19 feet of snow dumped on top of them, it did mean that Mono Lake was given a chance to rise, and all that water helped carry us through a lower risk fire season that was different from the severe drought the Mono Basin has suffered through over the past few years. 2022 was the driest first half of any year on record in the state of California, followed by the biggest winter on record. While the snow helps mediate the impacts from drought and fire, the whiplash weather events are signs that the impacts from climate change are becoming more readily experienced by this region.

Last year was a La Niña year, which often results in a colder and drier weather pattern for this region. It was colder, but drier clearly was not the case. As we move into the autumn months, I can look out my window and see the Sierra crest covered with a fresh dusting of snow; winter has already begun at the highest elevations. NOAA’s Climate Prediction Center recently released its projections for the upcoming winter. It is looking like we can expect an El Niño year, with the probability of a strong El Niño at 71%. While many people think El Niño means another winter of heavy precipitation here in the Eastern Sierra (like 1998), it can also mean a middling winter (like 2016), and it often results in a warmer winter with more rain and less snow. We will all be holding our breaths, shovels at the ready, eagerly awaiting more runoff for Mono Lake should these predictions hold true.

Top photo by Geoff McQuilkin: Massive amounts of snow blanketed the Mono Basin on March 25, 2023.